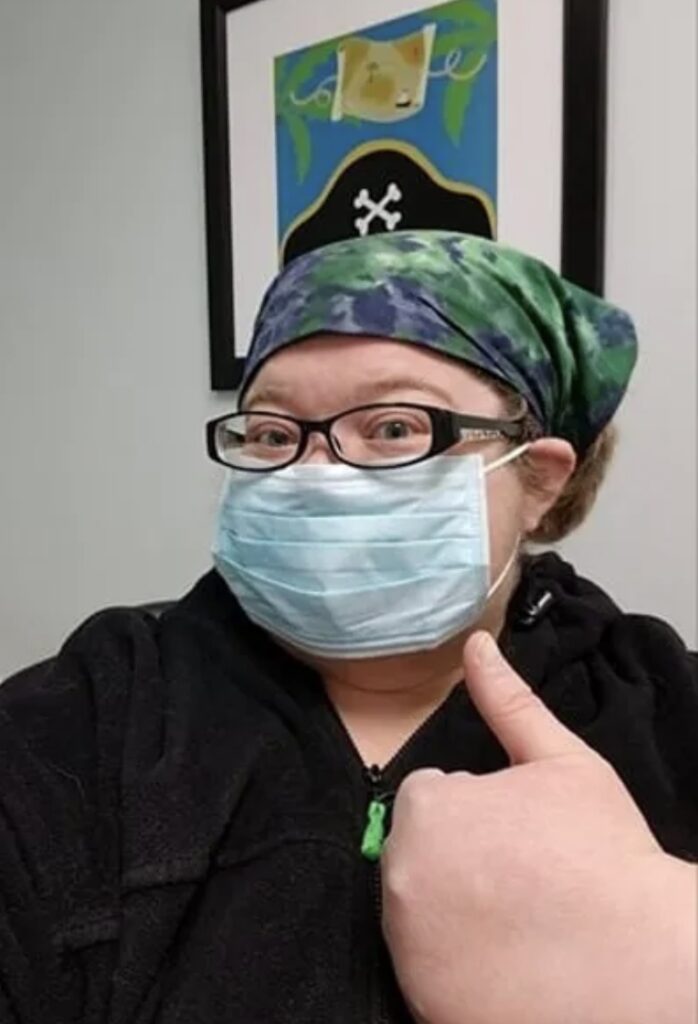

Lyllyan Blair

Throughout my childhood and early adulthood, I never gave much thought to mindfulness. Even during my short foray into Soto Zen Buddhism in my late teens, staying present, being aware of my body, emotions and mentality didn’t seem like something I should give much import to.

All that changed, however, at age 28. I was finishing my internship at a public school teaching a low-functioning, medically-fragile population of elementary students and working on my thesis for graduate school. Yet, suddenly, all that I’d planned for and worked towards became null and void. My whole life was turned completely around by the unforeseen onset of a rare neurological illness which left me physically disabled and visually impaired. It would take 1 ½ years for my eyesight to be completely restored and 3 years before I could walk again. I walked unaided for 15 months before my balance and mobility began to fail again. Since then, my prognosis is a slow regression of mobility though with no clear timeline. Since then, mindfulness has been forced upon me as a necessity and constant practice.

I have been a single parent for all 7 years of my daughter’s life. Since her birth, I’ve progressed (or regressed, if you’d rather) from a cane to a manual wheelchair to a power chair. Recently, she and I were both diagnosed with another rare disease; a genetic disorder of our connective tissue. Any parent must take inventory of their physical ability to handle a given situation. Yet, as a parent with 2 chronic illnesses, I must maintain vigilant awareness of how much sleep I’ve gotten and whether or not it was sufficient; I must take stock of any aches and pains that are either currently beyond or have the ability to surpass my pain threshold; I must ask myself if I have the energy I need and how I might feel after the birthday party, field trip, visit to the park, etc. Will joining in be something my body will pay for later? Will it drain me of energy? Will it cause new aches or worsen current ones?

It can be overwhelming trying to determine whether I can do something. I make mistakes often and must leave events early or I’m bedridden for a length of time afterwards. But I’m getting better at mindfulness. I’m learning more about my body. What’s surprising is that I’m not learning so much about my limitations as my capabilities. I’m stronger than I am weak. Mindfulness is a practice I think can strengthen us all, whether we’re disabled or not and whether we deal with chronic illness or acute ones.